March 2012

Forest Watch Students Building Research

TWENTY-ONE teachers and 14 University of New Hampshire scientists and administrators reviewed Forest Watch research achievements on February 4. The Annual Meeting highlighted new research initiatives by teachers and their students in white pine and sugar maple studies.

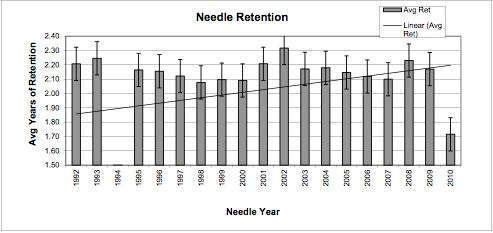

Research Findings For the first time since Forest Watch students began collecting data, the average needle retention on our white pines has dropped below 2 years. Teachers and their students found almost no second-year needles on their trees and very few second-year needles.

Teachers from throughout the region recalled June 2010 when white pines had massive losses of needles. Ozone or another powerful oxidant might be the cause of the needle loss. The UNH Extension suggested one of two fungi might have caused the problem.

|

This spring, as teachers and students check 2011 needles, they may find a few 2009 needles still on three-year-old stems. We hope these will give us clues as to whether the needle drop was caused by fungi or an atmospheric pollutant. The differences will be easy to see in a hand lens or microscope. The two fungi make distinctive marks on the outside epidermis of the needles. An atmospheric pollutant will cause plasmolysis or shrinking of the cell membrane inside mesophyll cells near stomata. We are very excited about this finding—a true scientific mystery.

Statistical Analysis by Concord High StudentsIn another first, the new 2010 Data Book publishes research by students at Concord High School and Gilmanton School. Last spring, students at both schools used Forest Watch data from the last 20 years of research to learn how to build statistical comparisons and correlations.

|

|

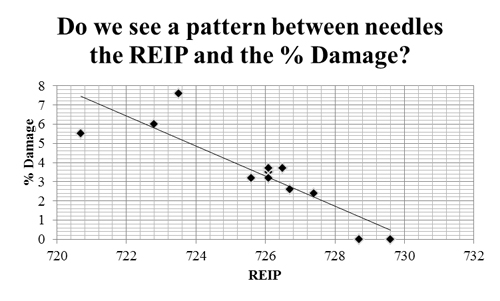

Patty Jared's 12th grade Advanced Placement calculus students took their AP tests in May. That gave them another month to explore statistics. With help from Phil Browne, Forest Watch's founding teacher and Patty's husband, students poured over 20 years of Forest Watch data. Teams of students pulled out sets of data to compare and consider. In some cases, the students found strong correlations between one measure of white pine health and another data set. For example, as ozone levels have dropped, white pine measures of chlorophyll as seen in the red edge inflection point (REIP) show a strong inverse correlation. In other tests, students found no correlations but learned a strong lesson in science: a hypothesis might not prove true.

Gilmanton SchoolSeventh graders in Mary Fougere’s class also tackled Forest Watch data. These teams asked bold questions such as “Are white pines at other schools as healthy as Gilmanton white pines?” In finding answers, these students learned how to graph data, to analyze results and present their findings.

Details about both schools’ work can be found in Chapter 6 of the new Data Book.

Both schools’ work is important. Students have delved into our data with new perspective, looking at data and testing hypotheses that the Forest Watch team at UNH had not done. More research by more minds is likely to discover new subtleties in the data.

Students working on research projects this year are invited to display posters and to discuss their work on May 25 at the 2nd Annual Forest Watch Convention at UNH. Read more…

Buoyed by these two schools' remarkable achievements, Forest Watch Data Books will feature more student research in the future.

Forest Watch Teachers Share Their Expertise

EIGHT TEACHERS shared their experiences with Forest Watch and inquiry-based science at the Annual Meeting.

New Horizons:

In Reflection on Inquiry Robin Ellwood, a PhD student who teaches at Rye Elementary School, Rye, NH, explained her research in measuring the quality of student thinking and analysis. When students are able to do hand-on experiential field studies, testing principles with real observations, their questions about the meaning of a concept are two or three times more complex than those framed by students who learn passively, she said. Robin is completing her research and thesis this year and hopes it will lead to school-wide programs at Rye Elementary.

|

|

In Standards and Inquiry Dr. Katherine Duderstadt, a high school physics and chemistry teacher, explained how Forest Watch activities could be meshed with new science standards for children in kindergarten through 12th grade. Kathy taught (until her recent move to Durham) in a standards-based school in Massachusetts. While many teachers wince at the thought of strict test-framed lessons, Kathy told how she found freedom to explore science and use applications such as Forest Watch with positive effect within the standards frameworks.

Kathy also applied Forest Watch to new technology, trying out our Data Book with a new Apple i-Book program. Our audience of teachers and UNH edcuators was wowed as Kathy zoomed us in and through the iBook software. More than an e-book, the new program allows the reader to zoom in and expand on any item on a page, zipping from text about ozone, for example, to a close-up view of chlorotic mottling.

Link to Kathy's work via https://sites.google.com/site/forestwatchideaskd/ Kathy wrote Forest Watch her thoughts after the presentation:

I felt honored to be included in a group of such enthusiastic teachers who exemplify what teaching is all about. The project/problem-based, authentic learning style of Forest Watch is so valuable to our children these days. This is especially true in an educational age that currently pushes standards-based and virtual learning.

I hope my brief presentation provided some ideas of how Forest Watch could satisfy some of the standards-based learning pressures that teacher face, while maintaining its original mission. Having come from Massachusetts where high-stakes tests often drive our curriculum, it is a challenge to maintain a connection to our natural world within daily science classes. I believe in the eventual goal of teaching the standards and preparing students for high-stakes tests while still allowing for scientific inquiry and authentic research through programs like Forest Watch.

I also think the iPad technology is very exciting, primarily because it is so teacher-friendly. IPads might be useful for Forest Watch not only in creating iBooks but also in on site spectral imaging of the trees using the iPad camera and photo applications.

Maple Watch Practitioners

Jon Marshall (at left) of the Josiah Bartlett School in Bartlett, NH, was one of four teachers to talk about their schools' sugar maple programs. Jon worked with Sarah Larson-Dennen and the Moharimet School in Madbury, NH, when that school built a post-and-beam sugarhouse. Moving to Bartlett, Jon carried the program with him.

|

Today students at both Moharimet and Bartlett tap sugar maples, collect sap, and help make maple syrup. In the process they learn about the history of sugar maples, the science of sugar and the math of reducing 40 gallons of clear sap to dense sugary syrup. Sarah's movie about Moharimet students clearly proves that children can build a connection with nature. Jon brought along not only a film of Bartlett's program but also his guitar. He played "I am the sugar man," a folk song that Bartlett students learn, tracing the sugar making process with every verse.

Math is a key part of the maple programs. Students calculate sugar content, sap to syrup ratios, and syrup production numbers each day during the season.

Bartlett and Moharimet teachers as well as teachers at several other schools are working with Martha Carlson, Forest Watch coordinator, to pilot activities in studying sugar maple health.

This spring, Maple Watch students are examining buds to analyze the health of their maples. Sugar maples put high priority on making excellent buds no matter how stressful a summer growing season might be. However, 2011 was extra stressful. Almost all older maples made seeds. That took a lot of sugar. This spring, buds are smaller than usual.

Students will measure the size of buds now during sugar season before the buds begin to swell. In April, they may measure them again each week to watch how the tiny buds grow. How will the leaves look when the buds open? Our Maple scientists will report what they find.

Scientists Visit Forest Watch

AN ANNUAL TREAT for Forest Watch teachers is the lectures UNH scientists give about their current work at the Annual Meeting.

Modeling Forest Health This winter Dr. Scott Ollinger, professor of biogeochemistry, talked about his latest work tracking carbon and nitrogen cycling in the New England forests. Dr. Ollinger uses hyperspectral remote sensing and field experiments to learn how increased levels of carbon and nitrogen in the atmosphere are affecting plant health. He is building complex models of plant respiration, atmospheric deposition and climate change to project future forest responses.

Dr. Ollinger is working with the GLOBE program to make such models accessible to teachers and their students. A current project is testing carbon cycle models and activities for schools. These will soon be available on-line.

Forest Canopies in the Amazon Dr. Michael Palace, a new member of the Natural Resources and Environment faculty, talked with Forest Watch teachers about his studies of forest canopies in the Amazon. Richer, healthier leaves, identified by their spectral reflectances, are growing on ancient terra petra, dark earths built by native Americans who lived in the Aamzon basin 500 to 1,000 years ago. Composted from animal waste, charcoals and leaf material, the terra petra is still fertile 500 years after people farming on the soils disappeared.

Dr. Palace's research opens up new questions about the history of the Amazon forest and its populations and develops new technologies which may be used to monitor forest health here in New England.

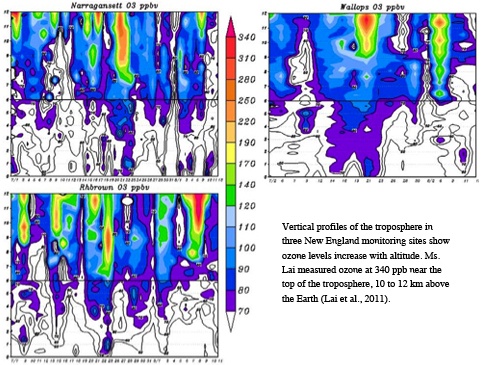

Ozone Conditions Are Changing Dr. Tzu-Ling Lai recently received her PhD at UNH for her study of ozone events in New Hampshire. Working with Dr. Robert Talbot, atmospheric chemist, Dr. Lai identified and documented several phenomenon which may influence tropospheric ozone levels in our forests. These include: The Bermuda High appears to have moved into the Atlantic, allowing cool wet air from the Gulf of Mexico to move north during our summers, reducing ozone events.

|

|

Unusual low atmospheric pressure events are allowing ozone in the stratosphere to pour into the troposphere, raising ozone levels when ground conditions would not normally produce ozone. Ozone may remain high at night due to transport of ozone from Midwest industries on a low-level jet stream.

Dr. Lai's study helps to explain why some of the highest ozone exceedance days in recent years have occurred in spring, fall or even winter. Read more about Dr. Lai's research at Lai, Talbot and Mao. The study also adds value to Forest Watch studies of white pine. Our new protocols will suggest that some schools may want to watch ozone levels regularly on AIRMAP, www.airmap.unh.edu, or the EPA ozone site, AIRNow,www.airnow.gov. Science labs might check white pine needles from just one easily accessible tree, to look for chlorosis and tip necrosis after any high ozone level events.

New Resources for TeachersThe GLOBE Carbon Cycle project is building activities in modeling for teachers and students. The Student Climate Data page is a pathway to activities with biomes over time, with Picture Post and climate data through time and for specific sites, such as one school. TESSE, another program, offers training for teachers in Earth Systems Science. All of these growing new programs can be accessed by searching GLOBE UNH

Growing the Data BaseOver the past year, 15 schools across New England monitored 74 white pines to study the impacts of tropospheric ozone on tree health. Students measured chlorotic mottling and tip necrosis on more than 7,000 needles. Fresh samples of their needles were also scanned in the UNH laboratory with the Visible Infrared Intelligent Spectrophotometer.

|

|

Louise James Wins Lauten AwardLouise James of Amesbury, Massachusetts, received the 2011 Gary N. Lauten Award for outstanding service and commitment to the University of New Hampshire's Forest Watch program at a ceremony held recently on the Durham campus.

Forest Watch is an inquiry-based science program that takes students and teachers out of their classrooms to study air pollution and forest health. Since 1991, more than 350 schools across New England have helped researchers at UNH to gather samples and measurements of white pine needles to monitor the impacts of tropospheric ozone.

James is a retired elementary teacher from the Sewall Anderson School in Lynn, MA. She used Forest Watch to build science into elementary school curricula, and with her students has been monitoring the health of white pines in the Lynn Woods Reservation for ten years.

Recalling the startup in 2002, James said, "At that time, the city did not have an official science program for elementary school. Each grade level had assigned topics but there were no materials or support provided by the city. Forest Watch enabled me to make science important to my students, and I was lucky enough to work for a principal who recognized my enthusiasm and was willing to let my work at UNH mold the science program at our school."

Soon, James was taking not only students but parents and other teachers into Lynn Woods where they learned much more than the science of white pines and ozone.

"I would begin each year with the message that 'Science is the story of how the world works.' Then I made connections: connections between the students and their world, connections between each science topic and other academic areas, and connections among the science topics themselves. I developed a reputation among the students that science in my class was fun," James said.

When funding for elementary science was cut in 2009, James continued Forest Watch as an after-school program, which she continues to do and also visits schools throughout the Boston area with Green Infusion, a trio that sings, rhymes and signs to teach children about nature and environmental issues.

Gary Lauten was a former Air Force lieutenant colonel who died in December 2001 and served as the Forest Watch program coordinator from 1992-1999. In 2002, the program began recognizing teachers who best exemplify Lauten's devotion to Forest Watch's long-term goals.

For two decades, Forest Watch has demonstrated that students can collect valuable data for ongoing scientific research and learn science and mathematics by doing research in their local area. Student data have clearly shown how responsive white pines are to year-to-year variations in ozone levels. NASA's New Hampshire Space Grant Consortium has sponsored Forest Watch since 1991.

"Over the years, I've been very impressed with how well student data mirror annual variations in air quality," says Forest Watch director Barry Rock of the university's Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans, and Space and the Department of Natural Resources and the Environment. "During a poor air quality summer, student data indicate poor tree health, but during a good air quality summer the data indicate improved tree health."

Rock notes that the annual award recognizes Lauten's commitment to making science accessible in the pre-college classroom. "He loved the program and became its heart and soul. And teachers love the program because it integrates biology with physics, math, Earth science, and chemistry.

More than 25 teachers attended Forest Watch's annual meeting recently in Durham. In the past year, students and teachers measured more than 8,000 pine needles and calculated their health and damage by ozone with over 1,200 different mathematical calculations. In the coming months, Forest Watch plans to train 20 new schools for the science program.

Summer Training Goes Out to TeachersForest Watch is thrilled to offer Forest Watch training workshops for new teachers in St. Johnsbury, VT, Bath, ME, Swanzey, NH as well as Durham. These workshops should enable teachers from the North Country, from central and Downeast Maine, and from southwest NH, southeast VT, and western Massachusetts to join us.

The three-day workshops will cover the science of ozone and white pine studies, an introduction to climate change and maples, field protocols, laboratory analysis, remote sensing and spectral analyses.

The workshops will cost $600 per teacher. Some scholarships are available.

Participantes in the workshops will receive a certificate for 24 professional development hours or 2.4 continuing education credits from the University of New Hampshire.

To register, fill out the registration form and email us at forestwatch@sr.unh.edu.

Veteran Forest Watch teachers are cordially invited to spend a day, June 22, with scientists at UNH learning the latest about their research, visiting labs and enjoying lunch with the scientists. Free. To register, email forestwatch@sr.unh.edu